Amsterdam

Case: Amsterdam Noord

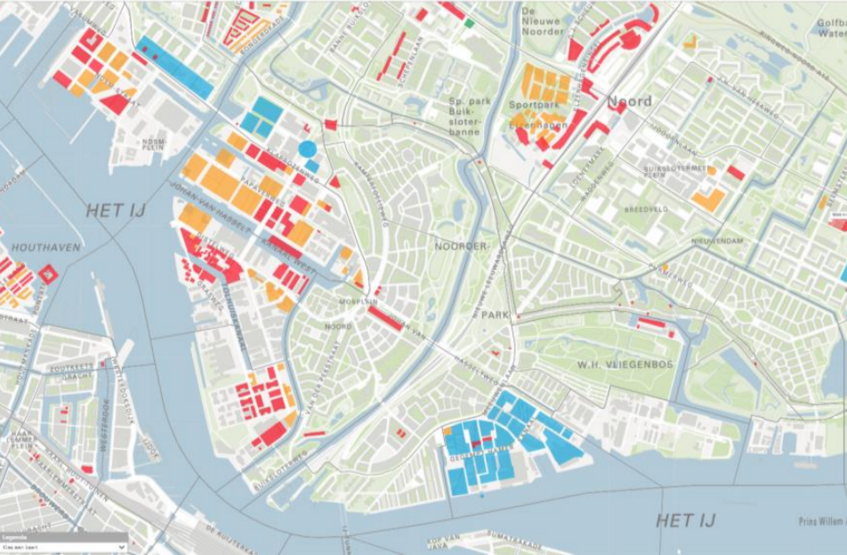

The progress of the Redevelopment Plan of Old-North in 2022: in red the areas where construction had began, in orange where permits were underway and in blue where the plans weren't definitive.

Case: Amsterdam Noord

Separated from the rest of Amsterdam through the waters of the IJ, the Northern district of Amsterdam has not only always been physically isolated from the rest of the city, but also culturally. The neighbourhoods in the Old-North were constructed in the 1920s and 1930s as publicly owned garden villages for the working class. Over time, ownership was transferred to housing corporations which are currently selling parts of their stock in this area. The discovery of the North as a site of real estate development should be seen in the wider context. Mainly as a result of immigration of international knowledge workers, Amsterdam’s population continues to grow, while the municipality faced the housing shortage with the ambition to build 52,500 to 70,000 homes before 2025. However, only a third of the newly planned accommodations are affordable rental units.

In apprehension of this ongoing brownfield gentrification of Noord, the network “Red Amsterdam Noord” (Save Amsterdam North) regroups local stakeholders to organize protest and demand political participation. As a result, the city co-planned the Masterplan North with the activists. After the promise of participation, the danger of co-optation has led to scepticism towards Red Amsterdam Noord and put the collaboration on this municipalist project on hold for some time. In 2023, the process was resumed so as to further develop and implement the Masterplan taking the local population’s interests into account.

Urban Living Lab in Amsterdam Noord

Neighbourhood coalitions

The Amsterdam Munex research examines the Northern Approach. After a successful political mobilisation by residents organised in Red Amsterdam Noord, which translates into Save the Northern district of Amsterdam, politicians, civil servants and residents together formulated the following overarching goals for this municipalist process: Together with the local municipality, citizens and other stakeholders develop plans for improving the quality of existing housing, for improving nature, green and public space and for decreasing social inequality by increasing equal opportunities and just outcomes. The living lab in Amsterdam specifically looks at the issue of decreasing social inequality and democratisation through inclusion of citizens.

To prevent double work and overload for participants, we take the municipal process itself as our living lab. Specifically, we here examine the development by the municipality of socalled neighbourhood coalitions in marginalised neighbourhoods of the North since the setup of this development closely matches the outline of our living lab. The residents of the North resist policy and scholarly terms such as 'lab' and 'experiment' which they state make them feel as lab rats in a laboratory. We thus henceforth refer to the living lab as a project. The goals to be achieved through developing the neighbourhood coalitions were formulated at the start of the project by the municipality as follows:

- to regain the trust of the citizens in the local government

- to work together with the residents rather than for them; to structurally change the way that the three groups of stakeholders of civil servants, social workers and residents interact

- to structurally decrease the inequality of opportunities in these neighbourhoods within the next twenty to twenty-five years.

- to adjust existing municipal subsidy streams towards the priorities of the residents

In each of the neighbourhoods a series of semi-public meetings took place, as well as a larger get-together for a broader audience. The research followed the development in the Molenwijk closest, hence the findings are most robust for that neighbourhood.